The Civil War

Maine entered the Civil War with a population smaller than that of most states, but answered the call for troops with a higher proportion of men than any other state in the Union. Approximately 73,000 Mainers entered the U.S. Army and Navy during the Civil War out of a population of 628,279 (1860 Census). The state of Maine would have an impact disproportionate to its size.

In 1861, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the Southern rebellion. Maine immediately began raising regiments of infantry and cavalry, as well as batteries of artillery. All the units raised by the state were strictly volunteer, in the proud tradition of the National Guard. By 1864, Maine had raised thirty-two regiments of infantry, two regiments of cavalry, and eight batteries of artillery. Maine men saw action in every battle with the Army of the Potomac, from First Bull Run to Appomattox. Maine units also participated in campaigns in Texas, New Orleans, the Carolina coast, and Sherman's March to the Sea. Maine artillerymen guarded the nation's capitol in Washington, DC, and Maine soldiers would serve as part of the occupying force after the war was over.

Women weren't allowed to serve in the Army in the Civil War but that did not stop some determined Maine women. Mary Jane Johnson served in Company I, 16th Volunteer Maine Infantry until she was discovered to be a woman after being captured at Fredericksburg and held in a Confederate prison. An unidentified woman served in the 14th Maine until she was found out, whereupon she faded into obscurity. Mary Ann Berry Brown of Lewiston accompanied her husband Ivory Brown into the 31st Maine Volunteer Infantry in 1864. While officially acting as a nurse, she dressed as a man and in post-war interviews she stated that she "carried a musket...and fought like the rest of them." She joined up, she said, because "slavery was an awful thing and we were determined to fight it down." After being discovered as a woman during the Siege of Petersburg, she stayed with the regiment as a nurse. She died in 1936 at the age of 98.

When Charles Sampson of Bath joined Company D, 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry as its captain in 1861, his wife Sarah Sampson packed up her things and accompanied the regiment off to war. Sarah accompanied the 3rd Maine through its major campaigns of the Civil War, including Gettysburg, working as part of the Maine Soldiers' Relief Association to care for the wounded. This kept her at or near the front lines through the war, acting as a nurse and assisting wounded Mainers far from home. She shared their hardships and struggles, not returning home to Maine until October of 1865. In 1866, she founded the Bath Military and Naval Orphan Asylum. She died in 1907 and is interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

African-Americans were at first not permitted to serve in the U.S. Army, and later were supposed to be restricted to segregated units with white officers. However, many in the communities in Maine turned a blind eye to color and many African-Americans served in white units, such as:

- Orrin Seco of China, 2nd Maine Cavalry

- Aaron Williams of Industry, Company G, 1st Maine Heavy Field Artillery, wounded in action

- Lemuel Carter of Bath, Company M, 1st Maine Heavy Field Artillery

- Franklin Fremont of Bath, Company M, 1st Maine Heavy Field Artillery

- George Freeman of Brunswick, Company M, 1st Maine Heavy Field Artillery, wounded in action

- Anthony Williams of Norridgewock, 30th Maine Infantry, killed in action

Ongoing research shows that many recruiters, officers, and their fellow soldiers in Maine units overlooked the regulations to allow these men to serve with honor.

Units

Maine units served with distinction across the board, but several stand out for their exploits and courage.

The 1st Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment was raised in Portland in 1861 out of existing companies of militia and was the first unit organized in Maine. They saw brief service as a 90-day regiment outside DC before they were mustered out. The regiment reenlisted as the 10th Maine Infantry, seeing action in the Shenandoah Valley and Antietam campaigns of 1862. Their enlistments expiring for part of the regiment, the remainder stayed on as the 10th Maine Battalion in 1863, with service at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. The unit was then consolidated with the 29th Maine Infantry, seeing service in Louisiana in 1864. Their lineage is carried on by the 133rd Engineer Battalion and the 251st Engineer Company.

The 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry was raised in Bangor out of existing companies of militia and was one of the first units to respond to Lincoln's calls for volunteers. Arriving in DC in the summer of 1861, it fought in the First Battle of Bull Run. Although the battle was a U.S. defeat, the 2nd fought bravely, and was the last unit to leave the field, allowing time for the rest of the army to retreat. The 2nd fought on through the campaigns of 1862 and 1863, compiling a record as a proven fighting unit. The 2nd Maine was later consolidated with the 20th Maine just prior to Gettysburg. Their lineage is carried on by the 133rd Engineer Battalion.

Raised in Augusta, the 16th Maine Volunteer Infantry fought through the war with the I Corps, Army of the Potomac. On the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863, the 16th marched through the night and fought a three hour engagement with attacking Rebel forces. The Confederate troops got so close that the men of the 16th were compelled to repel them with the bayonet. When the surrounding units began to give way, the 16th was ordered to, "Take that position and hold it at any cost." The 16th took up a defensive position and fought as a rear guard to allow the rest of the I and XI Corps time to escape. The 275 men of the 16th held off thousands of attacking Confederates, before being surrounded and forced to surrender. The men of the 16th destroyed the unit’s colors before they surrendered, so as to not let them fall into the hands of the enemy. They tore the flag into shreds and hid the shreds in their garments. Only thirty-eight men reported for duty the next morning. Their lineage is carried by the 133rd Engineer Battalion.

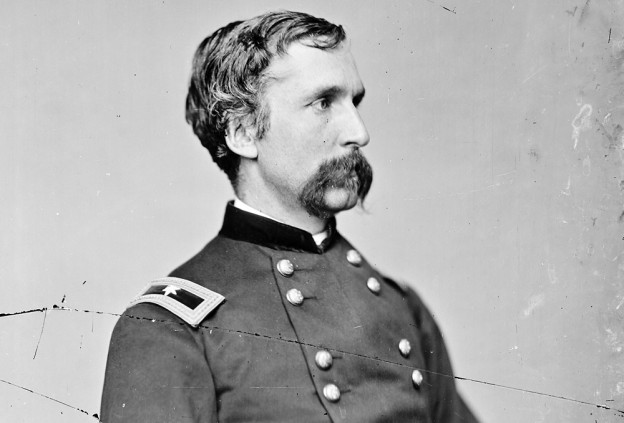

The most famous Maine unit was the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Raised in Penobscot County, it was part of the V Corps, Army of the Potomac. It proved itself under fire at Fredericksburg, staying the night on the cold battlefield pinned down under enemy rifle shots. On July 2, 1863, the 20th arrived on the field of Gettysburg, just as the Confederate assault was breaking the advanced U.S. lines. Colonel Strong Vincent, the brigade commander, ordered Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain to place his regiment on the far left of the U.S. line, holding a rocky spur of the hill called "Little Round Top." Vincent's orders were to "hold the position to the last." The 20th held the line against multiple attacks from three larger Confederate regiments from Alabama. At times the lines were so intermingled that Chamberlain could not distinguish the enemy's lines from his own. After more than an hour of combat, the men of the 20th began to exhaust their ammunition supply. Chamberlain knew he had to hold the line, and ordered the one thing he knew the enemy would least expect: a bayonet charge. All along the line men were given the order to fix bayonets. Chamberlain stepped to the front and gave the order: "Bayonets, Forward!" With that, the 20th charged down the hill, sweeping the surprised and exhausted Confederates in front of them. The charge saved the U.S. left flank and the important position of Little Round Top. The 20th would continue to serve to the end of the war, and was at the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865. Their proud heritage is carried on by the 133rd Engineer Battalion.

The 1st Maine Heavy Artillery was raised in the Penobscot River Valley and was assigned to the forts around Washington, DC. In 1864, it was withdrawn to move to the front to fight as infantry. In the Battle of Cold Harbor, the 1st "Heavies" joined in the U.S. assault on heavily fortified Confederate lines. It suffered the highest casualties in one attack out of any single U.S. Army regiment in the entire Civil War.

The 31st Maine Volunteer Infantry was the second-to-last infantry regiment recruited in Maine. It was immediately sent to the front lines in Virginia, where U.S General Ulysses S. Grant was besieging the city of Petersburg. U.S. Army generals decided that the best way to break the defenses would be to build a giant mine under the Confederate trenches. U.S. Army engineers and sappers built a tunnel under the lines and detonated the mine, causing an enormous crater. The 31st Maine was the first unit into the crater, and although the men fought hard, they were unable to break through. They suffered heavy casualties in this fight.

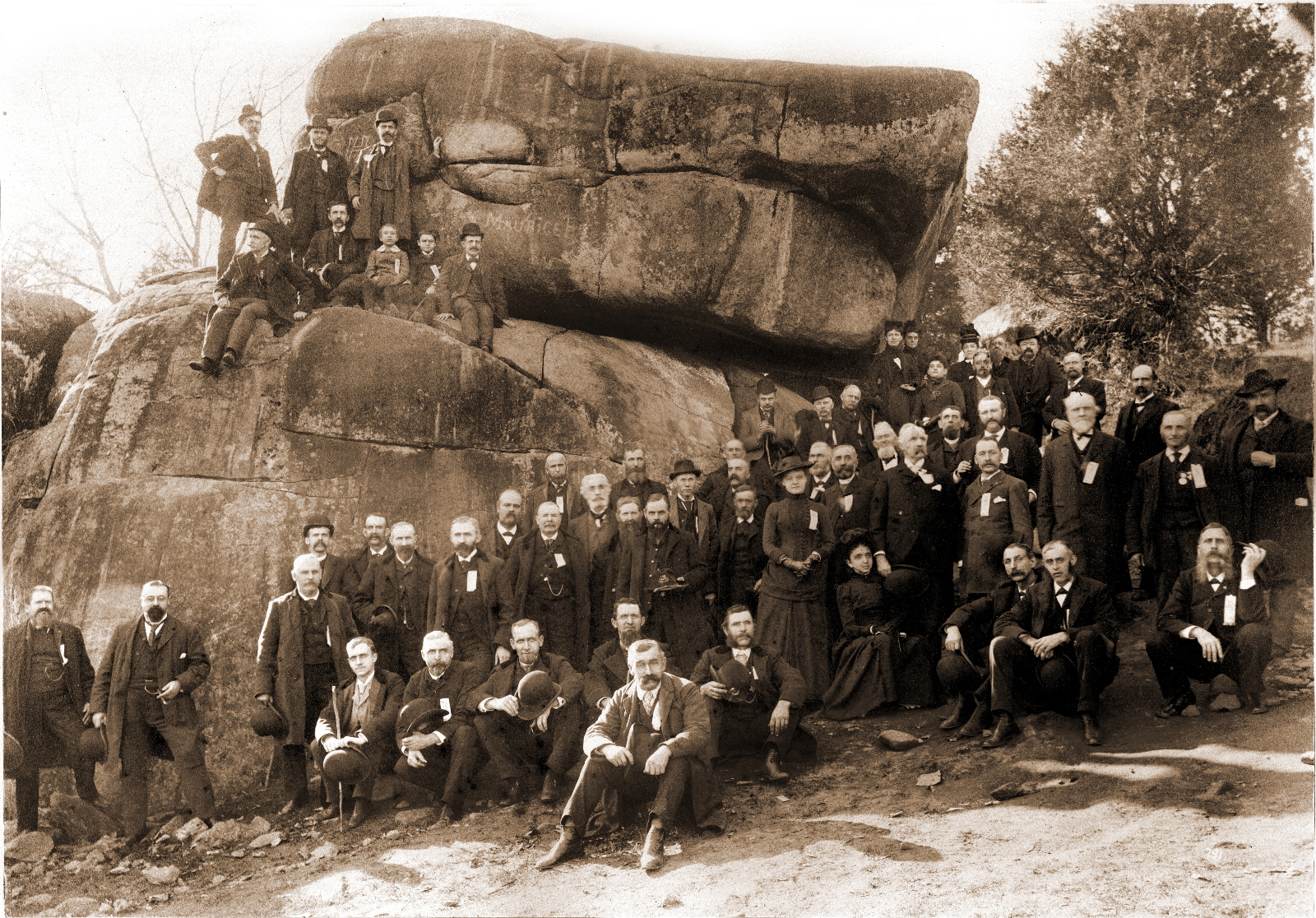

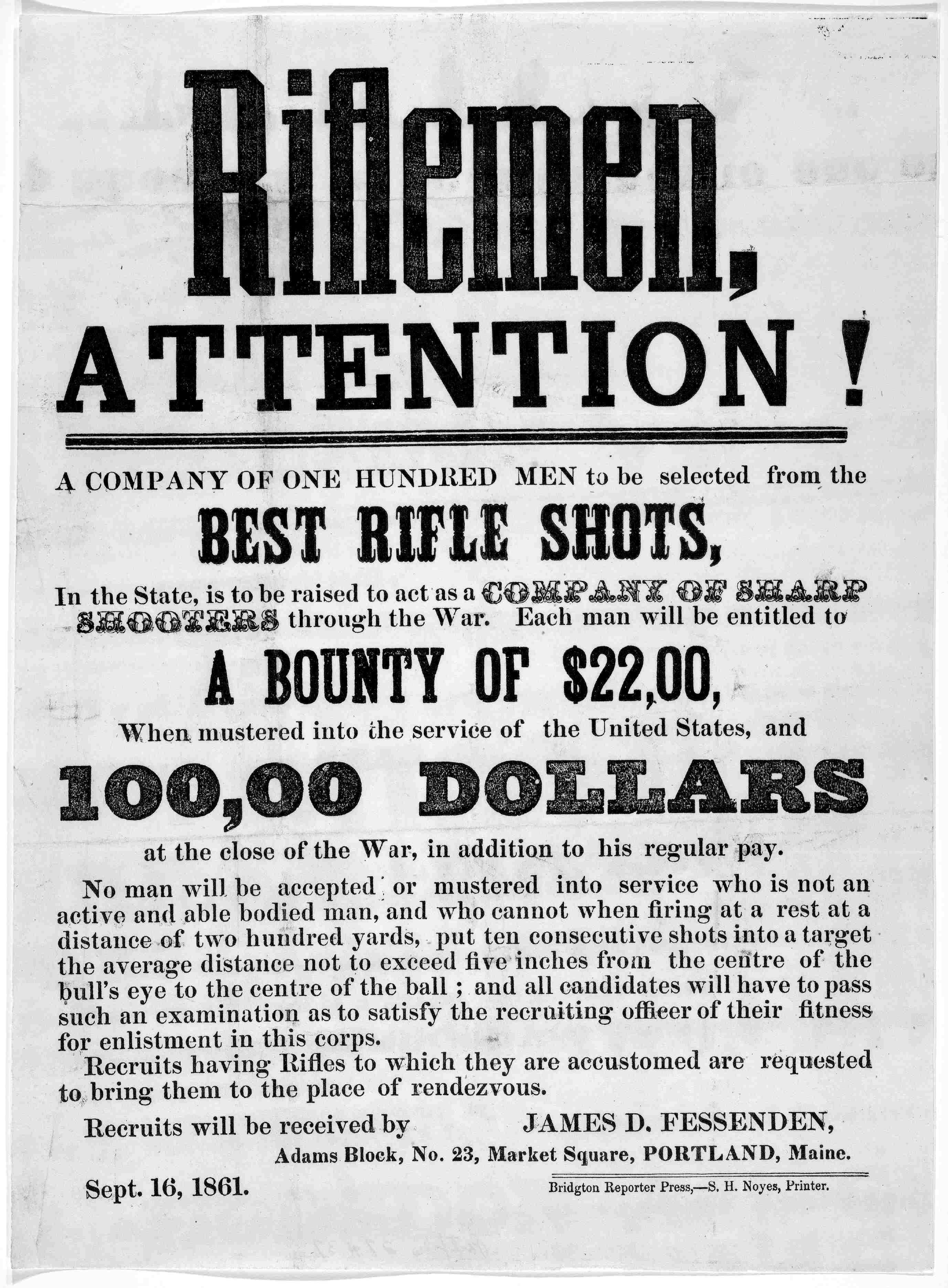

In 1861, the U.S. Army began recruiting companies of sharpshooters to act as specially trained Soldiers who would harass enemy lines with well-aimed fire from state-of-the-art weapons and act as scouts for the main body. One of the companies was recruited from Maine, as the quality of Maine woodsmen was thought to be desirable for such a force. The men were mustered in as Company D, 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters. They were extensively trained in light infantry tactics, were allowed to augment their uniforms to allow for more comfort and less noise, and were given Sharps repeating rifles. The 2nd served as a first-class combat unit, fighting in all the major battles of the Army of the Potomac. The qualities of the Maine marksmen were so sought after that Maine was allowed to recruit another sharpshooter unit later in the war, the 1st Battalion of Maine Sharpshooters. The 1st Maine Sharpshooters participated with distinction throughout the end of the war and their lineage is carried by the 133rd Engineer Battalion.

Leaders

Many leaders in the U.S. armies came from Maine. Many were graduates of the Military Academy at West Point and were already serving in the regular Army when war broke out. The leaders listed here exemplify the citizen-soldier, however, and show how civilian Soldiers from Maine were outstanding leaders for the U.S. Army.

George Lafayette Beal was the first man from Oxford County to enlist. He entered as a captain, commanding Company G, 1st Maine Volunteer Infantry. He was eventually promoted to command of the regiment, then the brigade, and ended the war as a major general of volunteers. After the war, he would serve as the 20th Adjutant General for the State of Maine.

Hiram G. Berry was the mayor of Rockland before the war. He personally assisted in recruiting the 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry and was commander of the 2nd at Bull Run in 1861. Within one year, he had been promoted to Major General and was commanding the 2nd Division, III Corps. He was killed leading his men in a counterattack at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. His loss was greatly mourned as he was one of the most promising battlefield commanders in the U.S. Army.

Freeman McGilvery was a ship captain from Prospect, Maine. He commanded the 6th Maine Battery in the campaigns in the east in 1862, including Antietam. At Gettysburg, now a lieutenant colonel, McGilvery patched together a line of artillery along Plum Run that halted the rebel breakthrough of the U.S. center on July 2. He died in 1864 as result of an accidental overdose of morphine during treatment of a minor wound. The first Saturday in September is Colonel Freeman McGilvery Day in Maine.

John Caldwell was the head of Washington Academy in East Machias when the war broke out. He enlisted when he was 28 years old, with no prior military experience. He was given the colonelcy of the 11th Maine Volunteer Infantry and saw significant action with the Army of the Potomac. He was wounded twice, led the largest Union assault at Gettysburg, and ended the war a major general. In 1865, he served as part of President Abraham Lincoln's funeral honor guard. Following the war he served as the 16th Adjutant General of Maine.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain is perhaps the most famous Soldier from Maine. Professor of Rhetoric at Bowdoin College, Chamberlain was one of the most patriotic men in Maine. When Bowdoin denied him leave to join the Army, Chamberlain took a leave of absence to study in Europe, and then joined the Army. He was made lieutenant colonel of the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry, under another Mainer, Adelbert Ames. Ames was regular Army before the war and taught Chamberlain the importance of drill and discipline. The discipline was needed when Chamberlain faced the momentous decision at Little Round Top: retreat, save his men, and lose the battle, or stay, but lose his regiment. Chamberlain chose the unthinkable, a bayonet charge right into the teeth of the enemy. Chamberlain was rewarded with a brigade command, where his displayed admirable leadership and coolness under fire. At Petersburg, in 1864, Chamberlain was leading his attacking brigade on foot when he was struck by several enemy rounds to the stomach. Despite the pain, he supported himself on his sword to encourage his men, before collapsing from loss of blood. Because most wounds of this type were fatal at the time, he was thought to be dying. General Ulysses S. Grant promoted Chamberlain to brigadier general on the field of battle. However, Chamberlain survived, in part because the men of the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry rushed him off the battlefield and the surgeon of the 20th performed immediate surgery. Chamberlain would go on to command a division, and would be selected to receive the surrender of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox in 1865. He would serve as Governor of Maine and president of Bowdoin College after the war, and honorary commander of the Maine Volunteer Militia.

Aaron S. Daggett, from Greene, was similar to Chamberlain in many regards. Rather than graduating from Bowdoin, he was a Bates alumnus, and had additional schooling in religious academies. He enlisted as a private in the 5th Maine Volunteer Infantry and rose through the ranks with astonishing rapidity. As a colonel, he was wounded at Cold Harbor in 1864. He ended the war as a brigadier general. Rather than leave the Army, he stayed in, becoming a captain in the 19th U.S. Infantry. Ranks from the volunteer Army did not transfer over into the regular Army at that time. Daggett fought out West, in the Indian Wars, and would go on to rise through the ranks fighting in the Spanish-American War, the Boxer Rebellion in China, and lastly in the Philippines. He earned a purple heart and the Gold Star for his valor. He became a brigadier general in the regular Army in 1900, retiring a year later. He died in 1938, the oldest surviving general of the war.

Maine campaign credit in the Civil War includes the following: Bull Run, Peninsula, Valley, Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Shenandoah, Appomattox, Virginia 1862, Virginia 1863, Tennessee 1863, Louisiana 1864.

Maine National Guard units with campaign streamers from the Civil War: 133rd Engineer Battalion and the 251st Engineer Company.