In the 1930s, the chief of staff of the 43rd Infantry Division, from Rhode Island, had gotten lost in Augusta, looking for Camp Keyes. He approached a smart looking youngster in front of the State House and inquired “Which is the street to take to Camp Keyes?

“Where?” asked the youth.

“Camp Keyes,” replied the colonel.

“Don’t know,” came the laconic reply.

“I mean where the soldiers are training,” persisted Col. Bissell.

“Oh, you mean the muster field,” said the youth, “why didn’t you say so?”

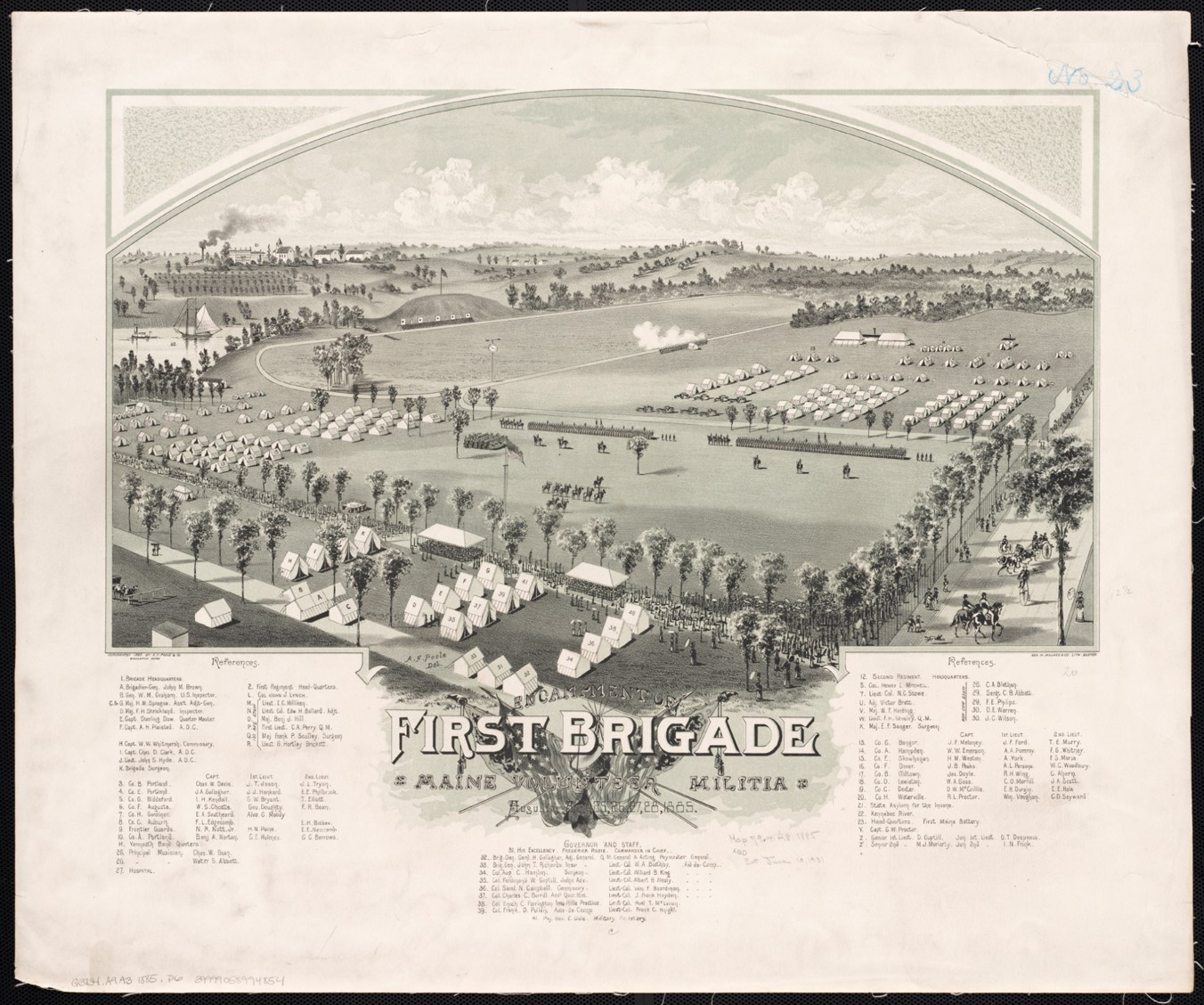

The official name of the site on top of Winthrop Hill in Augusta is Camp Keyes – but it’s also been known as The State Camp Grounds, the State Camp, or – for decades – the Muster Field.

The 70 acres on the broad plateau had long been used as a militia training area in Kennebec County, even prior to statehood. After 1820, it only made logical sense to have the militia train in a central part of the state, adjacent to state government. But it was the Civil War that would see the site formally entered into the legal framework of the state as a militia muster site.

General Order Number 34, dated 20 August, 1862, signed by The Adjutant General John L Hodsdon, designating three rendezvous areas “for drafted militia of the state and volunteers in lieu of the draft; and the following gentlemen have been appointed commandants thereof, with the rank of Colonel: John Lynch for the Rendezvous at Portland, which will be known as Camp Abraham Lincoln; George W Ricker (Rockland) for the Rendezvous at Augusta, which will be known as Camp E.D. Keyes; Gideon May for the Rendezvous at Bangor, which will be known as Camp John Pope.” The timing was not a coincidence – it was Lincoln’s call for 300,000 troops, the largest number of men under arms ever assembled in North America. Camp Keyes became the rendezvous for the counties of Franklin, Somerset, Kennebec, Sagadahoc, Lincoln, and Knox. Units that mustered at Camp Keyes include the 1st Battalion of Maine Sharpshooters, 1st Maine and 2nd Maine Volunteer Cavalry, nearly all the units of Maine artillery, the 7th, 8th, 9th, 11th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 21st, 24th, 28th, 29th, 30th, 31st, and 32nd Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiments.

Camp Keyes was also the site of the State’s only Federal Hospital during the Civil War. Named Cony Hospital after sitting Governor Samuel Cony, in 1864 alone, the hospital treated 2,500 Maine soldiers coming back from the seat of war in Virginia or out west, with 871 being returned to duty with their regiments, 55 discharged for permanent disability, 123 transferred to other hospitals, 25 died, and 13 deserted.

Incidentally, Augusta’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery donated land for the burial of U.S. soldiers who died within the town’s hospitals: 89 U.S. soldiers are buried there.

Post-Civil War, the entire State Militia mustered at the site for the first time in 1888 when the entire 70 acres was purchased by the State. The custom of the time was to name the camp after the sitting governor. This custom was abandoned in 1909 and the name Camp Keyes was made permanent.

The land proved incredibly suitable for encampments, with the Maine Central Railroad being less than a mile away. Small buildings were constructed of plywood for mess halls, kitchens, latrines, store houses, and lodging for senior military officers. Companies pitched their tents on pads that had been built.

From 1862 to 1938, the primary purpose of Camp Keyes was as the central training site for the Maine Volunteer Militia – which, by 1893, had become the National Guard of the State of Maine

Beginning in 1938, with the construction of the brick building on Winthrop Street, Camp Keyes took on a new role as the headquarters of the Maine National Guard. Up until this point, the headquarters had been in the state capital building. It would retain this role until 2018, when the headquarters moved officially to Camp Chamberlain where it is today.

Prior to World War I, the staff of the Adjutant General’s office consisted of just seven people. After WWI, it more than doubled to fifteen people. By WWII, there were over forty full-time employees, overseeing the over 4,000 Maine Guard personnel involved in WWII as well as the hundreds in the Maine State Guard, a home defense force used only during WWII and for a select time in the 1960s. The department was also responsible for the draft in Maine during both World Wars, working diligently to ensure that industry, agriculture, fishing, and other vital state services did not suffer from lack of skilled workers due to the draft.

Camp Keyes also housed the quartermasters and finance offices of the Maine National Guard from 1947, a role that the camp carries on to this day.

Camp Scenes

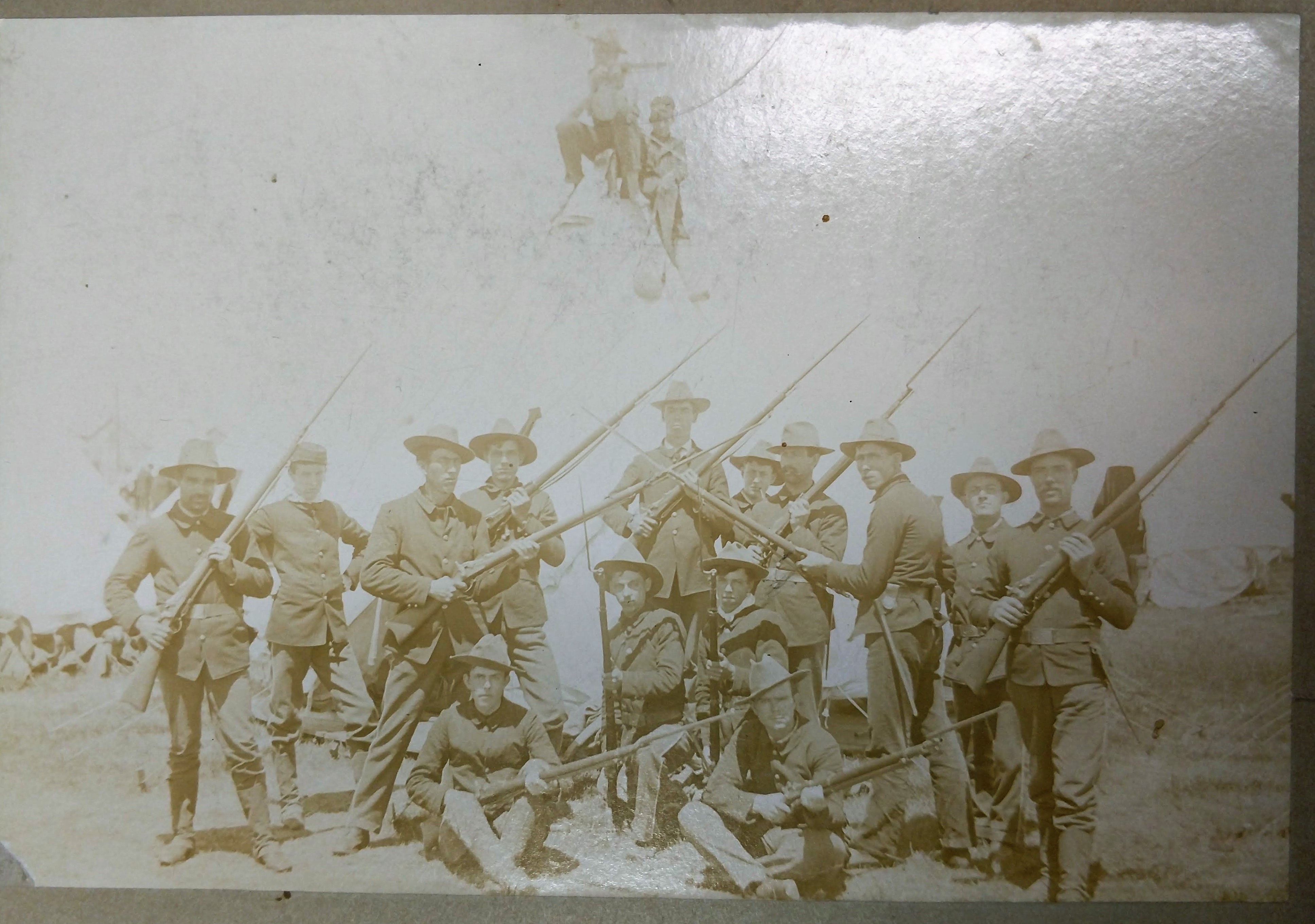

Here are some unidentified soldiers from the 1890s at Camp Keyes, armed with the 1874 Springfield trapdoor rifle. You can see the conical tents of the time pitched behind them – note the soldiers perching atop the tent.

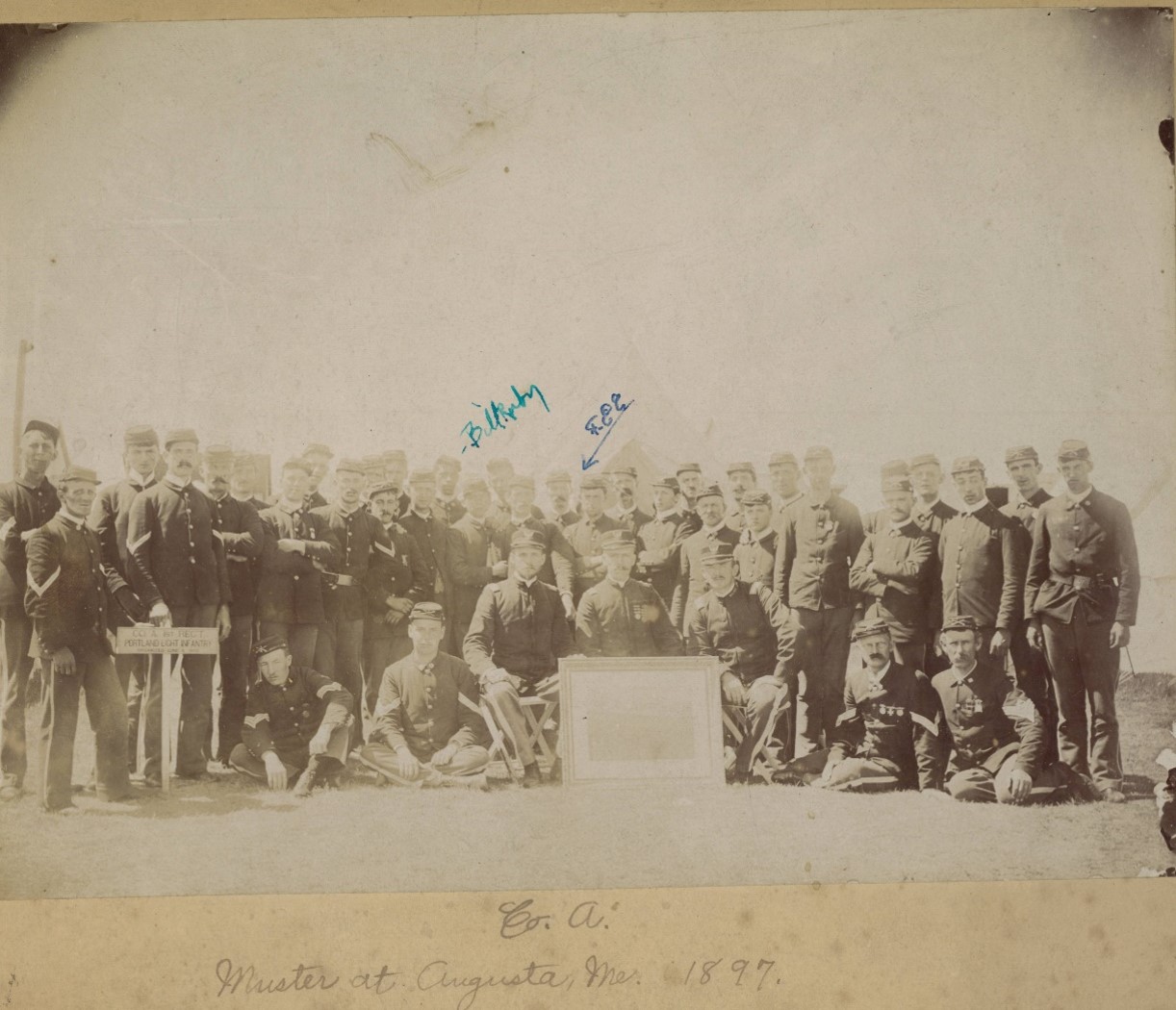

Company A of the 1st Regiment of Infantry, National Guard of the State of Maine, also known as the Portland Light Infantry. The oldest single company in the Maine National Guard, it is still in service now as the Headquarters Company, 133rd Engineer Battalion, tracing its lineage back to 1804.

Also from the 1890s, this quite fascinating little scene of camp being either packed up or being made. Of especial note is the bicycle in the foreground. The US military began experimenting with the bicycle as a mode of transportation for troops just before the turn of the century, and the National Guard followed suit. The Signal Corps of the Maine National Guard decided to experiment with bicycles in 1897. Fifteen troops rode bicycles while several more rode horses, from Portland to Augusta. Arriving at what was being called Camp Powers that year - after governor Llewellyn Powers – the two parties compares notes. Lieutenant George Butler of the Signal Corps left these notes:

“In my honest opinion, the cycle is entirely unfit for the purpose except in a country where the roads are good and even, and then only in daylight, for it is almost impossible to travel in the dark with full equipment without a lantern which is not to be thought of in a hostile country. Of the fifteen cycles that left Portland in a good condition, six tires were punctured, one crank broken, one frame twisted and rear brace broken, and one rim cracked.” This was the end of the bicycle in the Maine National Guard.

In 1898, the US and Spain went to war. On May 2, 1898, both the 1st and 2nd Infantry Regiments of the Maine Guard mustered at Camp Keyes, as well as the Signal Corps company. Troops here can be seen engaged in day to day camp life.

Officers’ school in Augusta, 1908. Prior to 1916, National Guard officers and enlisted soldiers could not attend the same training schools as their Regular Army counterparts, so states did the best that they could. Here are officers from both the infantry regiments at Camp Keyes. Note how the uniforms are transitioning away from the blue and towards the olive drab. Two years after the photo, the Maine National Guard would undergo a redesign. The 1st regiment of infantry would become thirteen companies of Coast Artillery, based out of the southern and Downeast counties of the State. Their training area would be Fort Williams in Cape Elizabeth. The 2nd Regiment of Infantry would continue training at Camp Keyes.

Governor William T Haines and The Adjutant General Albert Greenlaw, at Camp Keyes, sometime between 1913-1915. It was the tradition all the way into the late 1950s for the Governor to visit the annual encampment of the Maine National Guard.

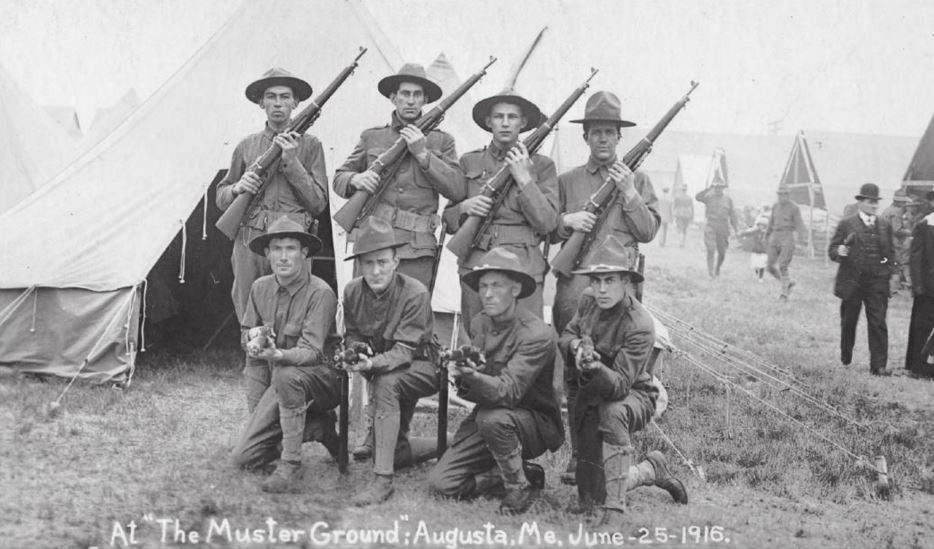

In June of 1916, the 2nd Maine was called up for active service. The violent civil war in Mexico was spilling across the border, with some factions actively encouraging attacks into the US in order to try to draw the US in on one side or another to resolve the war. What resulted was the call-up of 140,000 National Guardsmen around the US. The 2nd Maine Infantry was just one of many units called into service.

The regiment mustered at Camp Keyes in June of 1916 before departing for Laredo Texas. In October, the Maine soldiers would return home, mustering out again at Camp Keyes

But this was a short-lived respite. On April 6, 1917, the US entered WWI. One week later, a telegram arrive from the War Department ordering the 2nd Maine into service. From April to July, the regiment pulled guard duty across the state, as well as conducting major recruiting drives. 600 Recruits were brought to Camp Keyes and introduced to Army life: drill, military discipline, and customs and courtesies were the order of the day. Camp Keyes was bustling, with new buildings going up and new rifle and machine gun ranges being constructed

On July 5, 1917, Augusta underwent a marked change. Train after train pulled into the station all day long, as the sixteen companies of the 2nd Maine arrived, their time on guard duty at an end. 2,002 men – in all – now occupied Camp Keyes. Now assembled as a full regiment in Augusta, the 2nd Maine began to melding into a functional unit. They established a full training field at Camp Keyes, complete with dummies for bayonet practice and mock trenches. In the record-setting heat of July 1917 – temperatures were recorded in excess of 100 degrees Fahrenheit – the 2nd Maine set about its training regimen. This consisted of drill all morning, an hour of calisthenics at noon, and then field training until 5:00 PM. With the camp fully electrified, lights-out at 10:30 PM was adhered to with strict regularity, enforced by the first sergeant of each company.

Captain Arthur Ashworth’s Machine Gun Company set up a machine gun range in the southwest corner of Camp Keyes where they were able to practice their gunnery. Sunday parades livened up camp life as the citizens of Augusta assembled to visit their soldiers and watch them conduct skirmish drill, as seen here.

Family and friends visited every Sunday, to watch the regiment on parade and hear the band play concerts – the band, by the way, was that of the University of Maine, making it one of the few university bands in the whole Army.

This influx of soldiers of course brought money pouring into Augusta, as the soldiers spent their paychecks on everything from clothes and trinkets to pie and ice cream. Some $65,000 was spent on the very first payday that the soldiers had - for reference, that’s $1.4 million, with inflation. Soda parlors and pool rooms were full of soldiers, and every available single woman or girl seemed to have at least one olive-drab clad suitor, according to the Lewiston Evening Journal. The same paper reported that one of the lads from Bangor’s machine gun company ate “four yards of custard pie.” Just to paint a picture, here is an excerpt of the “special reports” coming out of Augusta that July: “All over the streets the boys were munching on fruit out of a bag, masticating the entrails of a sardine, pushing bananas into the front of their soldiers faces, or doing a figure eight on a big hunk of squash pie. They bough two peanut stands out clean, nothing but the roof and board floor left…There were one or two public dances in the outskirts of the city and every trolley car carried loads of soldiers bent on doing the dizzy waltz with some gently cavorting partner. The soldiers, such as participated in the terpsichorean maze, almost danced their leggings off.”

The specials from Augusta reveal much about life at the time…from the mascots at camp, like the ice-cream-eating black bear cub brought by Company K of Farmington, to the pro-women’s suffrage stance of the soldiers of the 2nd Maine.

Visitors from around Maine jammed the hotels and train station, pouring yet more money into the coffers of the city, Here, one can see the band performing in front of a packed field at Camp Keyes, with automobiles and buggies filling the landscape. As one paper put it, “Camp Keyes the Busiest Spot in the State.” On August 20, the Livermore Falls Advertiser ran the following: “Soldiers of Camp Keyes left for ‘destination unknown’ Sunday. In a downpour of rain that in mid-afternoon had been forecast by a bank of leaden clouds rising from the western horizon – conditions that seemed gloomily in keeping with the spirit of the occasion – the stalwart boys of 2nd Maine Regiment, U.S.A., departed from Augusta, and received the farewells that for many days past, parents, brothers, sisters, and sweethearts had been steeling themselves to utter with the same brave cheerfulness shown by the boys themselves…the streets of Augusta seemed strangely forlorn Sunday evening, with no young men garbed in olive drab to lend the atmosphere of youthful life which the citizens had come to feel was an inherent part of the city’s existence.” It took 106 train cars to move the regiment and its baggage from Camp Keyes down to Massachusetts. By October, the regiment would be in France and in the front line trenches by February. Of the men who left Camp Keyes that August, just around half would be killed, wounded, missing, or gassed.

Following WWI, the Maine National Guard was dormant for a year or two, until by 1921-1922, the units began to be reconstituted. The 2nd Maine had been renamed the 103rd Infantry Regiment in WWI, the designation it continued to carry into the 1920s. Camp Keyes continued to be an important place to train, as we see members of Westbrook’s Company D, 103rd Infantry in 1927, with their machine guns at Camp Keyes.

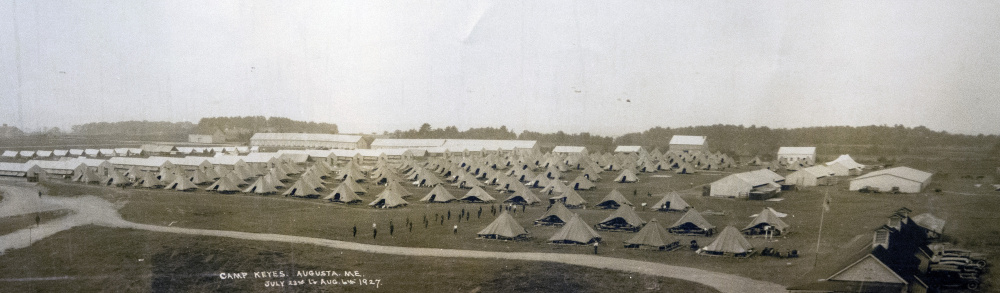

Camp Keyes, 1927, aerial view. The tents have improved, but most is still very much the same

The 1930s saw the Maine National Guard increase in size, with the addition of a large field artillery regiment in addition to the infantry regiment and coast artillery regiment. Maine also gained the headquarters for two brigades, part of the 43rd Infantry Division, one of the two National Guard divisions in New England. Here, Governor Louis Brann is greeted by BG Albert Greenlaw, commander of the 86th Brigade, upon his arrival at Camp Keyes, ca 1935-1937 In August of 1937, Camp Keyes saw 1,200 Guardsmen arrive from Maine, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Vermont, mustering at Keyes before leaving the state for a large exercise at what is now Fort Drum.

A new feature in the 1920s-30s was that the State Police began to conduct some training at Camp Keyes, such as this photo from 1938. The reason for this was two-fold: because the two organizations collaborated on state defense and civil authority issues, and also because the Adjutant General at the time, Brigadier General James W Hanson of Belgrade was both the The Adjutant General and the Chief of the State Police at the same time. This began a long tradition of collaboration between the Maine National Guard and civil authorities that was formalized in 1949 after the major natural disaster that were the Maine Forest Fires of 1947; this agency is now known as the Maine Emergency Management Agency, or MEMA

In addition, the Boy Scouts of Maine also began holding their jamborees at Camp Keyes. In 1937, over 3,000 boy scouts descended on the camp, attending the “third annual camporee of the Pine Tree Council of Maine” for three days in June. The scene was recreated in 1938.

Life at Camp Keyes was vitally different in WWII versus WWI. The 240th Coast Artillery Regiment was mobilized early in 1941 for duty on the seacoast. And while the rest of the state’s Guard was mobilized on February 24, 1941, for maneuvers in the American south, they mustered at Portland rather than Augusta. Without troops, Camp Keyes became a home for the 366th Infantry (an African-American unit), an MP training site, some prisoners of war, and served as a headquarters for the Maine State Guard. The Maine State Guard was a civil defense force authorized under the state Code as a part of the Military Bureau, to be used when the National Guard was deployed. Hundreds of Mainers served in the Maine State Guard during WWII, including many National Guard veterans who were too old and infirm for active service.

Following WWII, the Maine National Guard returned to business as usual. Here we see Camp Keyes, circa 1940-1950s, packed to the brim with GMC CCKW 2 ½ ton 6x6 trucks, also known as the deuce and a half. These were the iconic vehicles of WWII, and now the surplus could be used by the Maine National Guard.

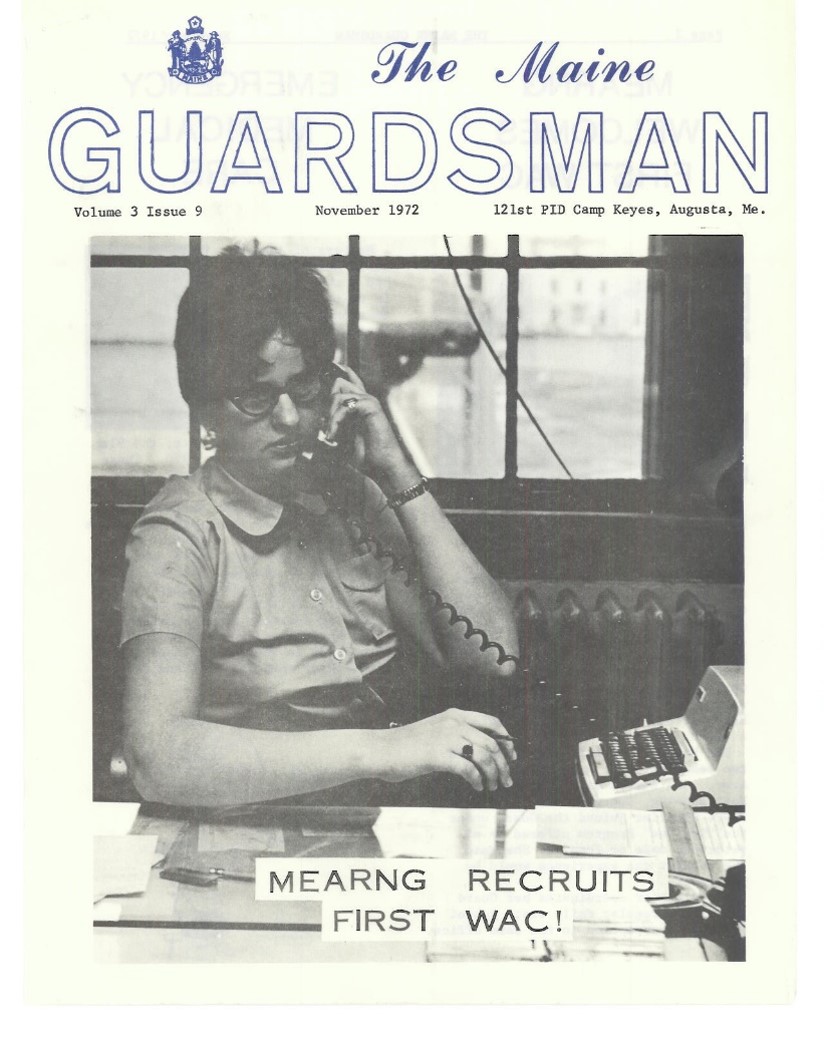

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the Maine State Troopers continued to hold their training at Camp Keyes. In 1972, the Maine Army National Guard recruited its first woman in uniform, Rita Cloutier, who worked full time as a personnel manager at Camp Keyes until her retirement in the 1990s.

Beginning in the 1960s, Camp Keyes became home to the Maine Military Academy (MMA), the state run school for officers and non-commissioned officers. Seen here in the 1980s, MMA would continue at Camp Keyes until the mid-2000s when it moved to Bangor as the 240th Regional Training Institute. Many officers in the Maine Guard through the 1960s-90s could claim their commissions through MMA.

Camp Keyes also served as an operations center for major events throughout the years. Here we see MEMA in action in the basement of Camp Keyes, during Operation Ice Guard, 1998. Camp Keyes also served as an operations center during the events of September 11, 2001. It remains an administrative and logistics resource for the rest of the state, as well as holding the Bureau of Veterans Services, the ID card office, and the barbershop.